The following key findings arose from a review of international research and a qualitative study of students’ experiences of a smartphone ban in schools within Ireland.

- International research suggests that smartphone bans have little or no impact on education, cyberbullying and wellbeing among students.

- Children and adolescents have access to many types of devices both in school and at home.

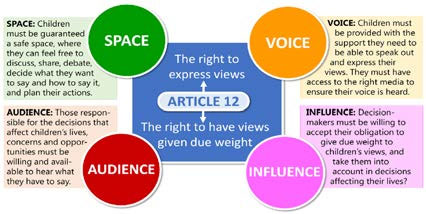

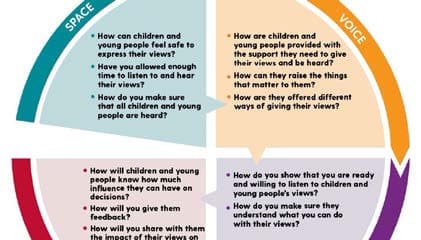

- Students’ voices have not been included in decision-making on smartphone restrictions/bans within schools and they want to have a say in decisions on this issue and other aspects of their school lives.

- Some students reported that teachers cause distractions to the learning environment with their phone use.

- Students are concerned that smartphone bans may inhibit students from learning resilience and skills for life beyond school.

- The stricter the phone ban the more students look for ways to subvert it.

- Students indicated that they were aware of different types of harmful content online but tended to minimise risks claiming that they felt able to self-regulate this content, ask for help, and trusted social media providers.

- There are more pressing issues for students than smartphone use in schools that students were concerned about, such as school facilities and health concerns.