Key Findings

The following key findings arose from a review of international research and a qualitative study of students’ experiences of a smartphone ban in schools within Ireland.

- International research suggests that smartphone bans have little or no impact on education, cyberbullying and wellbeing among students.

- Children and adolescents have access to many types of devices both in school and at home.

- Students’ voices have not been included in decision-making on smartphone restrictions/bans within schools and they want to have a say in decisions on this issue and other aspects of their school lives.

- Some students reported that teachers cause distractions to the learning environment with their phone use.

- Students are concerned that smartphone bans may inhibit students from learning resilience and skills for life beyond school.

- The stricter the phone ban the more students look for ways to subvert it.

- Students indicated that they were aware of different types of harmful content online but tended to minimise risks claiming that they felt able to self-regulate this content, ask for help, and trusted social media providers.

- There are more pressing issues for students than smartphone use in schools that students were concerned about, such as school facilities and health concerns.

Introduction

Currently in Ireland schools may decide to implement a policy according to their own needs. Arising from some concerns about anxiety levels, online bullying, and viewing of harmful content among primary school children, several initiatives have been introduced around the country by parent groups and/or schools intended to restrict smartphone use/ownership among children. While most schools operate an acceptable usage policy, other schools have chosen to implement different approaches by restricting and/or banning smartphone use. For example, some schools completely banned smartphones on school premises for all students, and others implemented more flexible policies.

In 2023, the Minister for Education provided guidance to parents who may have wished to engage their school community about internet safety and access to smartphones for primary school children (Department of Education, 2023). Last year, the Minister for Education announced her intention to introduce smartphone bans in post-primary schools while at the same time acknowledging that individual schools are best placed to decide on the scope and scale of restrictions for their students. However, the Irish Second-Level Students’ Union (ISSU) said it is opposed to plans that ban smartphones during the school day (McTaggart, 2024). The ISSU raised concerns and highlighted that most schools already have policies in place to combat the misuse of smartphones. In addition, they spoke about how there is a lack of engagement with second-level students on this issue.

In terms of bans, there are a variety of restrictions currently being implemented in Irish schools. For example, some schools have introduced locked pouches in which students must place their smartphone but have the pouches with them throughout the school day. Other schools require students to place their smartphones in a central box located in the school office or into a clear box on the outside of their lockers and students are allowed to retrieve their phones at the end of the day. Further, other schools allow students to keep their smartphones with them and they are trusted not to take them out of their school bag at inappropriate times. Finally, some post-primary schools apply a different set of rules for senior students. For example, allowing senior students to use their smartphones in designated spaces and times during the school day. Despite these ad hoc policies and bans emerging around the country, there is a dearth of research evidence in Ireland on the effectiveness of policies that ban or restrict smartphone use by children and adolescents in schools and whether the use of restrictive approaches (e.g., smartphone pouches in schools) or voluntary initiatives (e.g., no buying smartphones for children until post-primary) have a positive and/or a negative impact on students. As such, this current study set out to understand how existing smartphone bans are experienced and understood by students.

What does International Research say?

Despite the genuine concern among parents, teachers, and policy makers, there is limited evidence-based research to support the position that smartphone bans protect children from bullying and other online harms, as well as promoting their mental health. What research does exist tends to support some access to smartphones and studies that suggest otherwise are often found to over rely on correlations and/or overstate small percentages and/or causality to justify their conclusions.

Below, we report on some of the main findings from the existing international research on smartphone bans and related research on smartphones amongst children and adolescents.

Global Education Monitoring Report 2023 (UNESCO)

Some who support the introduction of smartphone bans in schools have referenced the Global Education Monitoring Report (UNESCO, 2023) claiming that it recommends banning smartphones in schools.

However, a full reading of the report reveals that it does not explicitly recommend banning smartphones from schools. Instead, it does acknowledge that some countries have implemented mobile phone bans or restrictions in schools due to concerns about privacy, safety, classroom disruption, and well-being (UNESCO, 2023, p.158). For instance, some schools in countries such as France, Spain, and the United Kingdom have introduced smartphone bans in the belief that they will improve academic performance and reduce distractions in classrooms.

Rather than advocating for a blanket ban, the report discusses the importance of establishing clear policies for the responsible use of technology. It suggests that effective policies should include transparency, clarity, and evidence-based decisions while ensuring that students are educated on the risks and opportunities of using technology.

The report emphasizes the balance between managing risks associated with technology and preparing students for a digital future, rather than universally banning devices like smartphones in schools.

PISA Data

In the PISA 2022 survey, school administrators were asked to report if there was a smartphone ban in their school [i.e., the use of smartphones is not allowed on school premises] (OECD, 2023). Kemp and colleagues (2024) analysed the responses and found that when the percentage of schools that ban phones in a country is plotted against mean results in science, mathematics and reading for that country, a statistically significant but small negative trend exists (p < .001***, R ² = .13). They found that for every 10 per cent increase in the number of schools in a country banning phones, PISA scores fall by 0.09 of a standard deviation, or 9.4 points. In other words, the higher the percentage of schools in a particular country that have bans in place for phones, the lower that country’s average PISA score.

Additionally, they found that OECD countries appear to perform very differently from non-OECD countries, getting higher science, mathematics and reading results on average, and being less likely to implement bans. Kemp and colleagues (2024) found that when gender, social class, and school behaviour are controlled for, students in schools with smartphone bans have lower achievement across their PISA test scores than those in schools that allow phone use. Based on preliminary analysis of the PISA data, the researchers concluded that when considering a smartphone ban, the relationship between a range of variables – not just student distraction – should be investigated to support policymakers in deciding to implement smartphone bans in schools.

United Kingdom

A recent study by Goodyear and colleagues (2025) undertook a cross-sectional observational study with adolescents from 30 English secondary schools, comprising 20 schools with restrictive and 10 with permissive policies. The study found that restrictive school policies did not lead to lower phone and social media use, nor better mental wellbeing outcomes in adolescents. The researchers concluded that there is no evidence to support that restrictive school phone policies, in their current forms, have a beneficial effect on adolescents’ mental health and wellbeing or related outcomes.

A quantitative study by Beland and Murphy (2016) examined exam scores in post-primary school students and found that in schools that implemented a mobile phone ban, the ban had slightly better results for underachieving students but had no significant effect on high-achieving students. Beland and Murphy (2016) suggested that the most likely explanation for this difference is that low-achieving students may have poorer self-control and become distracted by the presence of mobile phones, whilst high-achievers might be more focused in the classroom regardless of the mobile phone policy.

Another study in the UK involved a large-scale test of the so-called Goldilocks Hypothesis to examine the relationship between digital screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. The findings demonstrated that moderate use of digital technology is not intrinsically harmful and may be advantageous in a connected world (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017).

In addition, other researchers in the UK presented a critical account of the shortcomings of the literature on screen time (Kaye et al., 2020). The authors highlight that existing research on screen time showed mixed results and there is a lack of longitudinal evidence for casual or long-term effects. Further, the authors outline that a shortcoming of literature on screen time includes poor conceptualisation of what screen time is, as there is no universally accepted definition amongst experts. Thus, it is difficult to determine what is specifically meant by screen time, as it is a quite vast conceptualisation.

It is unsurprising that the authors highlighted that there is a wide variation in self-report measures used to capture screen time (Kaye et al., 2020). For example, some studies have examined ‘total screen time’ in respect to a certain timeframe (e.g., in the last week), whereas other studies ask about estimated amount of screen time on a school day and non-school day. Other studies take a different approach by asking participants about what type of device they use or their activity (e.g., passive use/TV viewing, social media use etc) or focusing on one specific technology use or the use of a specific platform. This wide variety of questions asked to participants may account for the mixed findings on screen time and its impacts, particularly among adolescents. Finally, it is important to note that self-report measures are common practice in social science research, however evidence suggests that they can be particularly ill-fitting for gaining accurate information on an individual’s technology related use (Ellis, 2019; Sewall et al., 2020).

The largest study ever of internet use and wellbeing, which involved 2.4 million participants in 168 countries found that on average, across countries and demographics, individuals (including children) who had internet access, mobile internet access, or actively used the internet, reported greater levels of life satisfaction, positive experiences online, experiences of purpose, and physical, community, and social well-being, and lower levels of negative experiences (Vuorre & Przybylski, 2023). The researchers in this study found that their results did not provide evidence supporting the view that the Internet and technologies enabled by it, such as smartphones, actively promote or harm well-being/mental health.

USA

Researchers from the USA utilised two nationally representative surveys of more than half a million adolescents in the USA to examine screen time on ‘new media’ (including social media and electronic devices, such as smartphones) and mental health impacts (Twenge et al., 2018). The authors concluded that adolescents who report higher levels of screen time were more likely to report mental health issues. However, more recent research and meta-analyses demonstrate that there is conflicting evidence on screen-time, use of technology and mental health impacts amongst adolescent samples.

One major review of existing research in the USA (Ivie et al., 2020) focused on social media and depression among 11–18-year olds concluded that social media is one of the least influential factors predicting adolescents’ mental health. In fact, the most influential factors include family history of mental illness, early exposure to adverse experiences, and family-related stressors.

A more recent study from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2023) on ‘Social Media and Adolescent Mental Health’, found that available research that links social media to mental health shows small effects and weak associations, which may be influenced by a combination of good and bad experiences. The research team concluded that contrary to the current cultural narrative that social media is universally harmful to adolescents, the reality is more complicated than this narrative suggests.

Recently another meta-analysis from researchers in the United States and United Kingdom on 46 studies on adolescent social media use and mental health (Ferguson et al., 2024) found that current research is unable to support claims of harmful effects for social media use on adolescent mental health (e.g., anxiety and depression). The researchers highlighted that there were methodological issues with the current research and recommended that caution should be taken when attributing mental health harm to social media use for adolescents, as the current evidence does not support this.

Further, these researchers highlighted that it is not unreasonable for parents to ask questions or be concerned about their adolescent’s social media use, however, parents are currently being misled by unsupportable rhetoric from some policymakers and professionals to believe that the evidence for harm is greater than it is (Ferguson et al., 2024). Finally, these researchers advocate that policymakers and professionals should adopt more cautious reporting standards when discussing social concerns which the evidence for is weak.

Sweden

Researchers in Sweden replicated Beland and Murphy’s (2016) study by conducting a quantitative study investigating whether smartphone bans had a positive impact on academic performance (Kessel et al., 2020). That study found no impact of smartphone bans, either positive or negative, on student’s academic performance and rejected small-sized gains. Notably, Kessel and colleagues (2020) collected data from the entire country’s population of 15–16-year-olds, unlike Beland and Murphy (2016) who only sampled participants from four UK cities. Echoing Beland and Murphy (2016) in the UK, the authors suggest that on the face of it banning phones looks like a “low-cost” solution and such bans should not be expected to change the basis of students’ performance drastically.

A qualitative study in Sweden on student experiences of smartphone bans found that students were left balancing their phone usage with the teachers’ arbitrary enforcement of policy. The researchers concluded that, despite this, smartphones are increasingly becoming a resource in the students’ infrastructure for learning (Ott et al., 2018).

Australia

Recently, two leading experts from Queensland University of Technology and The University of Queensland in Australia, along with a team of researchers, conducted a scoping review on global evidence for and against banning mobile phones in schools (Campbell et al., 2024). The aim of this review was to examine whether student mobile phone use at school is beneficial or disruptive to engagement and learning and investigate the impact of using mobile phones at school on academic outcomes, mental health wellbeing and cyberbullying. Global research on mobile phone bans improving academic performance is conflicting, as the authors cited that reconciling the results was challenging and findings should be treated with caution due to the differences in methods and measures, as well as discrepancies with operational definitions of the bans. Due to this complexity, interpretation of findings that may inform policies requires a nuanced approach.

Further, this review by Campbell and colleagues (2024) found that research examining the relationship between attitudes to mobile phone use (i.e., correlational relationship) and student learning is mixed, as some studies demonstrate that bans help improve learning and other studies do not show any improvement. Interestingly studies, which were conducted in different settings, found that students prefer to have autonomy with their phone use at school regardless of the policy, with many reporting that they use their devices despite the bans (Gao et al., 2017; Howlett & Waemusa, 2019; Walker, 2013).

In this review (Campbell et al., 2024), studies that explored the evidence to support smartphone bans in schools for protecting student mental health and wellbeing were inconclusive. Further, research supporting smartphone bans for reducing bullying and cyberbullying is also divided. The review’s authors stated how crucial it is to recognise that banning mobile phones and not banning other internet connected devices in schools is a simplistic solution that is unlikely to have any meaningful impact.

In addition, if a student wants to cyberbully another student, they could use any tool available to them at school, such as laptops, tablets, smartwatches or library computers. It is also important to note that cyberbullying often happens outside of school hours and off school grounds (Smith et al., 2008) and is usually an online expression of offline bullying (Wolke et al. 2017). In addition, by banning phones there is a risk of driving cyberbullying behaviour underground or making students more underhand (Brewer, 2014). The review by Campbell and colleagues (2024) concludes by recommending that policymakers and school administrators should emphasise the importance of teaching critical digital literacy skills and responsible device use in schools. Without this vital education and support to safely navigate online spaces, providing children and adolescents with unrestricted access to smartphones potentially places them at greater risk of harm from digital predators or harmful content.

Summary

The international research outlined is clearly mixed and somewhat conflicting, with most studies showing that smartphone ban policies can have little or no impact on education and wellbeing among students in different countries.

Considering the combined findings of international studies, regulating smartphone use at school requires further research on the effectiveness of policies, particularly exploring what will meet the students’ best short-term and long-term interests. In addition, no current research can be said to definitively demonstrate that smartphone bans completely protect children and adolescents from online bullying or harmful content. Furthermore, there is no research evidence that students do not use other devices to bully each other or to access harmful content if there are smartphone bans, considering that most schools use laptops or iPads within the classroom, and most children have access to a device at home. Thus, these justifications for a smartphone ban are not supported by current evidence-based research.

Current Study

The main aim of current study is to understand the experiences and understanding of students in Irish primary and post-primary schools where bans are in place.

The data was collected by a team from the DCU Anti-Bullying Centre between April and June 2024.

The team chose to undertake qualitative research for three reasons:

- It is not possible to undertake a pre/post study to assess the impact of restrictions/bans without raising serious ethical issues and over a longer period than the time allowed for the study.

- The researchers were concerned with the real lived experience of the students where restrictions/bans were in place and as such qualitative research methods allowed us to obtain a deeper understanding than surveys and other quantitative methods.

- The current debate around children’s and adolescents’ smartphone uses in schools and beliefs around its negative impacts have mostly only included adult voices. The voices of children and adolescents have been absent, and the researchers wanted to hear directly from them.

Ethical Approval

There were several ethical issues to be considered for this study. Firstly, confidentiality and anonymity for participants. Secondly, ensuring the safety and wellbeing of students, and thirdly, ensuring that researchers did not lead or introduce any bias into the data collection and analysis.

Consequently, the research team considered the best methods and approaches to use in recruiting participants and conducting focus groups with students. All research procedures were designed to align with government guidance on developing and conducting ethical research with children (Department of Children and Youth Affairs, 2012). The current study was approved by Dublin City University’s Research Ethics Committee prior to commencing data collection. The research project received a full committee review and written permission was sought to conduct research from all schools participating in the study.

Participants

Participants were recruited via a purposive sampling strategy across 6 schools that were a mix of co-educational, single-sex, fee paying, mainstream, and DEIS schools. Focus groups involved 66 students (44 girls and 22 boys) aged between 10 and 18 years of age.

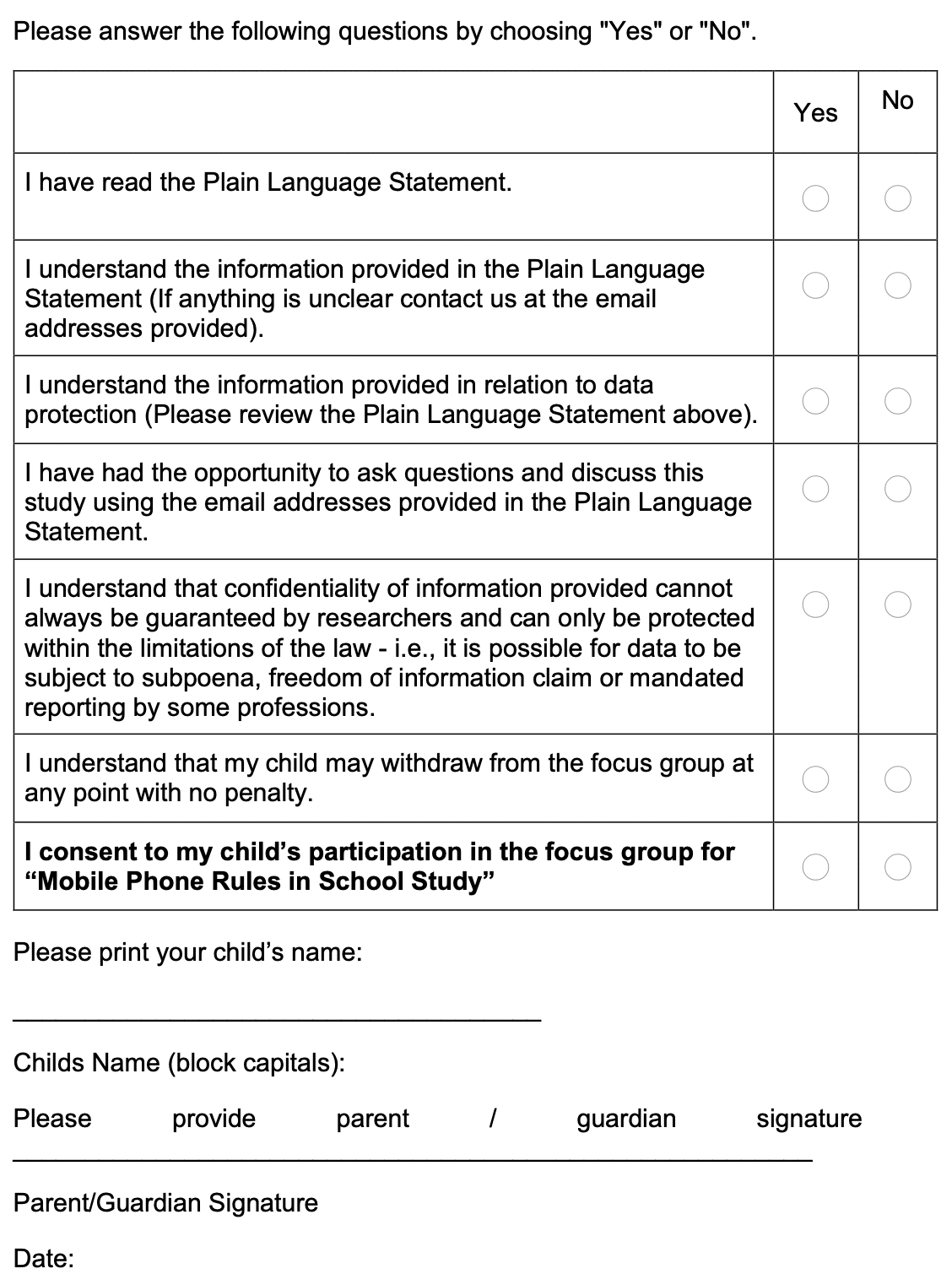

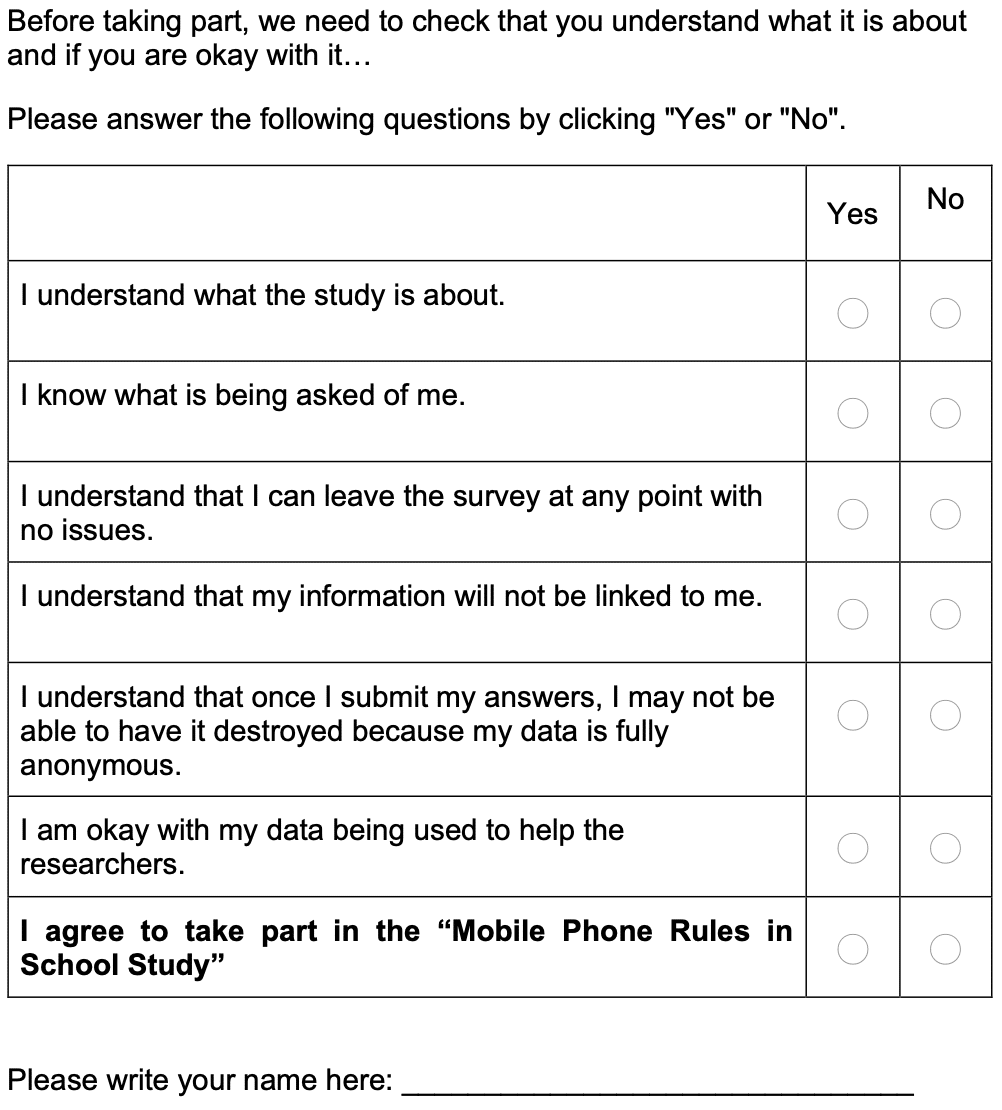

Consent

In advance of the focus groups’ consent was obtained from each student’s parent/caregiver (see Appendix 1 for further detail). On the day of the focus groups, students were asked to consent and informed that they could withdraw at any point without consequence. Students were provided with age-appropriate plain language statements and consent forms which included information on what the study would entail, storage of data, limits to confidentiality, anonymity, and contact details for support if they required it at any stage during or after the focus group (see Appendix 2 and 3 for further detail). Any student who was 18 years old provided their own consent.

Study Design

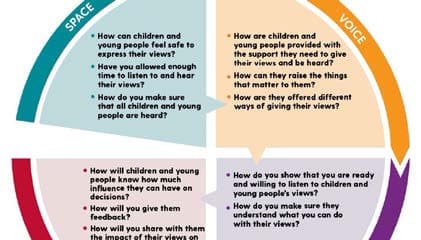

The researchers conducted focus groups with students in schools. The focus groups were based on the Lundy Model of Child Participation (2007), which is based on four key concepts (i.e. Space, Voice, Audience, and Influence). Students were engaged in discussions about their experiences and understanding of smartphone bans and this provided insights into whether these bans or restrictions have been effective within schools. Schools are not named within this report to protect participants’ confidentiality.

Focus Groups with Students

Participants were informed that a voice recorder was being used to facilitate transcription of what they said in focus groups and that the recording would be destroyed after the data had been transcribed. The focus groups were held in a private classroom on school grounds. Both researchers and participants sat in a circle, as it encourages interaction and facilitates a more comfortable and open discussion amongst a group. One researcher facilitated the focus groups and the other two researchers acted as moderators. The focus groups began with icebreakers, which were utilised to ensure that participants began to feel comfortable. The icebreakers used in the focus groups are explained in greater detail below. Researchers developed an interview schedule (see Appendix 4 for further detail), but participants were able to lead the discussion within their groups, and the researchers asked follow-up questions to clarify any comments. The interview schedule was only used to pose further questions to prompt discussion if the group was slow to engage. At the end of the focus groups, participants were provided with debrief sheets which contained contact details for support organisations should any student feel they required them. The researchers took notes individually during and after all interviews. Any personal information was removed to maintain confidentiality.

Icebreaker

An icebreaker activity was utilised in this study because they help participants build trust, feel more open to begin a conversation, and encourage participation (Chlup & Collins, 2010). The icebreaker activity chosen for post-primary students utilised news clippings discussing smartphone bans and asking participants what they thought of these news headlines. This icebreaker activity was chosen due to how relative it was to the main discussion of the focus groups. The image below depicts an example of a news headline that was utilised in the focus groups.

For the primary school participants, photo elicitation was chosen, as it prompted discussion amongst participants on smartphone use. The image below demonstrates what was used for photo elicitation with the primary school students.

The Lundy Model

In line with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, researchers used the Lundy Model of Child Participation as a framework for the focus groups with student participants in this study. The model involves four core components that should be adhered to during data collection with children and adolescents, which can be seen in Figure 1. below.

The research team ensured that they adhered to the Lundy Model by using the following checklist in planning and carrying out the focus groups:

The ongoing debate on smartphone use by children and adolescents has been dominated by adult concerns on the potential or perceived dangers of smartphones and social media, which in turn seeks to justify smartphone bans in schools. Children and adolescent voices and perspectives have been largely absent on an issue that directly impacts them. Thus, it was important for the research team to implement the Lundy Model to ensure that children and adolescents had space, voice, audience, and influence when participating in this research. Further, this report marks the first time that children and adolescents’ voices have been heard on this issue in an empirical study in Ireland.

Analysis Approach

Reflexive thematic analysis was utilised to analyse the data from the current study, as it is an easily accessible and theoretically flexible interpretative approach to qualitative data analysis, which facilitates the identification and analysis of patterns or themes in a given dataset (Braun & Clarke, 2012). Further, this approach acknowledges the researcher’s active role in knowledge production (Braun and Clarke 2019a). Thus, codes represent the researcher’s interpretations of patterns of meaning across the dataset. The process of coding (and theme development) is flexible and organic and often evolves throughout the analytical process (Braun et al. 2019b).

The analysis followed six phases. Phase one involved familiarisation with the data, which entailed reading and re-reading the entire dataset. Phase two involved generating initial codes, which produced succinct and shorthand descriptive labels for information that was relevant to the research questions. Phase three reviewed and analysed how the different codes that shared similar features may be combined to form potential themes or sub-themes. Phase four involved reviewing potential themes. Phase five presented how the researcher must define and name themes. All themes must create a lucid narrative that is consistent with the content of the dataset and information relevant to the research questions (Byrne, 2022). Phase six involved the write-up of the themes, which are presented in the findings section below.

Findings

Smartphone bans had been in place for at least one academic year in all the schools that participated in this study. Overall, students expressed frustration that they were not consulted about the introduction of a ban within their school and highlighted the complexities with smartphone use in their lives. Please note that we have separated the findings regarding students into post-primary and primary.

Types of Smartphone Bans

While smartphone bans were in place in all the schools that participated in this study, each of the schools involved in the study had different approaches to a smartphone ban. Post-primary schools used Yondr and PhoneAwayBoxes, and primary schools used voluntary smartphone codes arranged through parents.

Yondr

Some schools utilised Yondr pouches, which are grey pouches that hold smartphones and have magnetic locks at the top that can only be opened by teachers. Below shows an image of a Yondr pouch.

In schools that utilise the Yondr pouches, students must put their smartphone into the pouch and lock it at the beginning of the school day. In the policy of some schools, students must demonstrate putting the phone into the pouch and lock it in front of their teacher.

The image below shows the lock of the Yondr pouch that students must close in front of a teacher in some schools.

Once closed the Yondr pouches are supposed to only be opened with a specific device, which can be viewed in the image below. Schools varied considerably on how they implement the pouch opener. For example, one school hangs several pouch openers near the school gates and on benches at the end of the day for students to open their pouches. Another school has teachers, who have class at the end of the day, bring openers to class, which allows students to open their pouches before they leave school. Further, another school has the Yondr opening device locked behind a black box, which is mounted to the wall. The door to the box is opened before classes start but is then locked until the end of the day. Please see images below for the Yondr pouch opening device and a black box that holds the opening device.

Yonder Opener (left) and Pouch (right)

A closed black box which contains a pouch opener

PhoneAwayBox

Another approach found in some schools was what is known as a PhoneAwayBox. Students in this school must put their phone into a clear plastic case and lock it. As seen in the images below, students have a combination key for their PhoneAwayBox, and students must use their code to open the box.

Lockers

Voluntary Codes

Primary schools have taken a different approach to post-primary schools. For instance, the primary schools who have taken part in the present study have utilised a voluntary smartphone code. The voluntary code was led by parents often with the support of the school. Parents/guardians sign up for the code and state their intention to not buy their child a smartphone until they are in post-primary. Parents/guardians can access information on how many other parents/guardians have signed up to the voluntary code. It is important to note that block phones with no internet access were not included in any of these codes.

Post-Primary Students Perspective

Benefits and Drawbacks of Smartphones

During discussions on the role of smartphones in their lives, students expressed a nuanced view. Most of the students stated that a benefit of having a smartphone is the independence and safety it provides, with one student explaining:

Another student echoed this sentiment on safety:

Other students talked about other benefits to smartphones, such as:

For students across all focus groups, smartphones are intrinsically linked with their life and assist in maintaining friendships, providing safety, and learning. Thus, smartphones are not viewed by adolescents as inherently bad or dangerous, instead they understood that smartphones can be used for good or bad activities and/or behaviours.

One student explained how adolescents can see the benefits and risks of social media, whereas adults only have a negative perception of social media:

In another focus group, one student said that they had never seen any adults provide proof of their concerns, which made it difficult to understand adults’ perspectives:

Lack of Student Voice & Agency

Most students indicated that they were not consulted before or after the introduction of a smartphone ban in their school. For example, one group told us that:

In a different focus group, one student discussed how there is a mixed view on the ban in their school, but highlighting how they had not been consulted about the ban:

Other students informed us of the reasons provided to them for the ban being implemented in their school:

Students indicated that they abided by the previous mobile phone policy and would not use their phone during class time. However, they now felt that they were being punished for the bad behaviour of a few others and that this was not fair. Students felt that those who broke the rules should be the ones who are punished. One student explained this position:

Others explained that there had been restrictions in place before the ban, which were adequate, and they also felt that the ban was unrealistic when, similar to adults, smartphones are already blended into their daily life. They were frustrated that they had not been given an opportunity to explain this to those who introduced the ban in their school:

As highlighted above, most students said that they were not consulted about the smartphone ban and, in most schools, teachers have not asked for their opinions on the ban since it was implemented. This led into a wider discussion on how students generally have little say about what happens within schools, whether that is with regard to uniforms, facilities, what is taught and learned, and school policies. Most students expressed frustration at the limited role student councils had in their school. Students said that teachers or the principal retain all the power to make decisions.

One student said:

Students stated that they have no voice in decisions and have no other recourse but to do what teachers tell them. Students said that schools disempower them and indicated that their opinions are unimportant, particularly on any policies or initiatives that directly impact them. A small number of students even expressed that a smartphone ban in their school is in direct contention with their rights as a child.

For example, one participant stated:

Students felt that there was more people in power could do to elevate the student voice and agency, with one student explaining:

Students also discussed that in the cases of trying to contact home or go home from school due to being sick, they felt that teachers do not take students seriously. One student said:

Further, students rejected the perspective of parents and teachers that the ban will allow students to be more social with one another. Students felt that they should have autonomy over who they become friends with and it is up to students to decide if they want to make more friends. One student explained:

Further, students rejected the perspective of teachers that the ban will allow students to be more social with one another. Students felt that they should have autonomy over who they become friends with and it is up to students to decide if they want to make more friends. One student explained:

For the majority of students in this study, they felt that school staff (Teachers, Secretaries and Principals) do not hear students’ opinions on issues that directly impact them, nor do they feel as if their voice is important. Students want to be listened to by adults and believe that more could be done to elevate their voices on issues around school life, including the use of smartphones.

Preparation for a Blended Life

Students said that they felt that the ban did not teach them anything useful, as it did not prepare them for life and work outside, and after school. They spoke about how they were not building digital literacy, critical thinking, resilience and social skills around phone use. One student explained that:

This student went on to further explain that a ban in school would remove a safe space where adolescents can learn about the online world and make mistakes at an age where it’s more socially acceptable for mistakes to happen, and are close to adults who can support them:

Another student, in a different focus group, brought up how they believed that adolescents are not taught critical thinking skills when it comes to social media:

Other students expressed that if they aren’t receiving education on how to safely use social media then they are at risk of harm whilst on these platforms outside of school:

Students further explained that a ban will mean that they will not learn when it will be appropriate to use and not use smartphones in social settings. For example, students stated that when they are in college or employed that their smartphones will not be restricted, as they are expected to have learned when it is appropriate to use their phone.

One participant stated:

Another student explained that students needed more support and felt that a ban would make it more difficult for adolescents to understand and deal with situations regarding smartphones:

Resisting the Ban

Resistance to the ban was common among students, who achieved this through a variety of means. One student explained why they believe students resist the ban:

A fellow student further explained how other students resist the ban in their school:

This was reflected in another school where students said that it was common to break the ban:

A main rationale for implementing the ban was to prevent students from accessing their phones and reduce distractions in school. From the conversations with students across different schools, it is evident that students are finding ways to access their phones during the school day and are often distracted by thinking about how to access their phone. In fact, we found that the stricter the ban the more intensely students sought ways to subvert it.

Different Rules for Teachers

There was a perception among students that teachers were not obliged to follow the same rules for their smartphone use in schools. Students reported that they had seen teachers in class using their smartphones and on social media apps. For example, one participant said that they had seen their teacher in the classroom:

Another student had witnessed teachers on their phones throughout the school day:

Students highlighted that teachers do not model the behaviour they require from the students in this regard, as they tell students how they cannot have their phones, Students argued that teachers do not model the behaviour they require from the students in this regard, as they tell students how they cannot have their phones, but teachers can use their phones whenever they want. Further, students said that teachers often disrupt class with their own phone use:

Students were very exercised that teachers are not leading by example, particularly as they have told students how concerning smartphone use is in schools.

Better Use of Funds

Students across all schools minimised the importance of potential problems with smartphones and reported that there are more pressing issues in their schools that need to be addressed. They highlighted issues they experience with facilities in schools (broken toilets, quality of school meals, uniforms), as well as concerns about health issues. For example, one student brought up a pressing concern for them:

One group of students unanimously stated that they felt the money that the school had spent on Yondr pouches could have been put to better use:

Another group of students stated that vaping was a bigger problem in their school. One student stated:

From the students’ perspective, they experienced more immediate problems with school facilities than they did from smartphones. Students said that such concerns were more pressing and should have been dealt with first rather than focusing on banning smartphones in schools when there had already been a mobile phone policy in place.

Complexity & Vulnerability

Students emphasised how complex their lives can be and that the introduction of smartphone bans showed a lack of recognition of this by schools. One student explained:

In one focus group, there was a discussion on how adults, particularly teachers, do not acknowledge that students can have significant responsibilities at home. One student explained that:

Students wanted school policies to be flexible and recognise that they cannot always leave their home lives outside of school.

Students indicated that they do not always feel comfortable nor safe in disclosing personal issues to teachers, as they view many teachers as unfamiliar to them. One student explained why they felt this way:

Another student in a different group explained why they do not feel comfortable discussing personal issues with teachers:

In one school, with a smartphone ban, students reported that where they used to be able to make a quick call or send a text to a parent if they were unwell or had emotional issues, they now had to inform their class teacher, then the school secretary, and then the deputy principal before being allowed to make a call home. They reported that this led them to feel over exposed and vulnerable.

Minimising Online Risks & Adult Concerns

Although many of the students in this study reported that they were aware of occasional cases of cyberbullying, they explained that they felt that that smartphone bans do not prevent cyberbullying and that adults were overly concerned about this issue:

Further, students criticised adults who, they said, often amplify a situation because they were not aware of the context in which young people communicated with each other on smartphones and other devices:

They said that they felt that adults use extreme examples to over-inflate risks around smartphones. In one focus group, students explained their feelings on adults’ concerns about young people on social media and smartphones in schools:

Another student explained:

Other students, in a different focus group, felt that online bullying would not occur during school, and it is more likely that it occurs outside of school thus banning smartphones in school was pointless:

One student stated that they felt it was easier to view the smartphones as the issue rather than delving deeper into issues concerning adolescents:

Students warned against adults presuming that smartphones were to blame for the increase in adolescents being diagnosed with anxiety and depression, and instead pointed towards access to better information on mental health:

During the focus groups, students explained how adults are often more concerned than they are about the risks that can occur when using social media. They explained that technology has been a bigger part of their life compared to previous generations who may be more fearful and less equipped to respond to risks.

Many students also said that they go to friends for support about problems on social media, as they feel that parents do not fully understand social media or adolescents’ online spaces:

Most students indicated that they had a high level of trust in social media companies to protect them whilst online. For example, in relation to algorithms and safety strategies on social media apps students explained:

Throughout the focus groups in post-primary schools, most students indicated that they understand how algorithms work and have trained the algorithm to give them content they are interested in. Further, students engage safety strategies on social media apps to ensure that they remain safe whilst using these apps. Interestingly, students stated that they have a level of trust that social media apps will restrict harmful content to keep them safe when online.

Students felt that technology and social media is intrinsically blended into their lives and should not be viewed as an add-on, believing that many adults do not understand this. In fact, as highlighted above, students feel that adults are not comfortable with technology/social media and do not understand it enough to support adolescents when they encounter issues online, instead they report that adults often “overreact” and amplify issues more than is necessary.

Digital Citizenship Education

Despite the provision of considerable resources for digital education in schools, students reported that they were not taught enough in school about online safety and digital citizenship leading them instead to rely on their peers for guidance and skills:

Students further explained that using a smartphone can in fact increase their digital literacy skills and resilience, with one participant explaining this and reporting that education in school is mostly confined to computer skills more than digital citizenship:

Students showed an eagerness to learn more about online safety, as well as skillsets of good digital citizenship.

Primary School Students Perspective

Access and Familiarity to Smartphones and Social Media Apps

Like the responses from the post-primary students, primary students also reported that they received their own phone when they were 11 or 12 years old. They also informed us that the reason they received a phone was because they were going into post-primary school and parents wanted to ensure that they had the phone for safety reasons, particularly travelling to and from school.

Students did inform us that from an early age, parents had provided access to other devices, such as an iPad. Students have access to social media apps through those devices; thus, it is not solely smartphones that provide access to social media apps for children and adolescents.

Primary school children who participated in this study attended schools where smartphones are not allowed due to parent initiated voluntary codes, which are aimed at delaying providing smartphones to children. Parents sign up to the code when their child begins primary school. Despite this, students were easily able to identity different types of smartphones (i.e. Android or iPhone) and revealed that they were frequent users of them. Students were asked how they could tell the difference, with one student explaining:

Another student explained how they could tell the difference between the make of the phones:

All students identified that the phones had icons for social media apps and informed researchers of apps they recognised:

Students then explained which apps they used, with most students saying they used YouTube explaining how they access this app with one student stating they access it:

In one focus group with primary school students from 6th class, they all reported that they had a smartphone but some also explained why they did not bring it to school:

However, members of this group did go on to express some frustration explaining that there were times they need access to a phone, specifically for travelling to and from school and attending appointments:

Another student said:

It was evident from the focus groups that if children did not have their own phone that they had access to a phone or a device within their home. Similar to post-primary school students in this study, the primary school students used phones or devices for entertainment (e.g., watching YouTube videos or shorts), completing homework and mostly to communicate with friends.

Student Acquiescence

Students were clear on why their parents did not allow them to have their own phone while in primary school repeating what they had heard from their parents:

Students who did not have their own phone talked about what they might use one for when they go to post-primary school:

Another student in this group felt that they would need a phone to have more independence in post-primary school:

Interestingly, primary students did not seem overly concerned about cyberbullying and reported that it was not something that had happened to them or anyone they knew.

In relation to spending too much time on a phone, students expressed trust in their parents to guide them on how to regulate their usage:

These younger students seemed to rely less on smartphones and other devices instead spending more time on school and/or other leisure activities such as sports, dance, and playdates.

Another student said:

Overall, it seemed that these primary students had yet to develop a realisation about the scope of content and activities that can be accessed on smartphones and were more inclined to engage in offline activities that preoccupied them, relying on their parents to mediate the online world for them.

Learning about Online Safety

Primary school students stated that they learn about how to be safe online from the internet itself, their parents and in school:

One student said:

Students reported that online safety lessons were delivered by teachers and outside speakers. However, while primary school students seemed to have a higher awareness of digital safety education than post-primary students, they also expressed some frustration in that they said the information is repetitive and they watch the same safety videos each year:

Overall students in primary schools said that they mostly relied on their parents to learn about online safety.

Student’s Advice to Minister for Education

In line with the Lundy approach to children’s participation, students in primary and post-primary were asked what advice they would give to the Minister for Education regarding smartphones in schools.

Student responses covered topics from the introduction of a new policy on smartphones to the provision of education on digital wellbeing. One student said:

Another student believed that the previous more flexible school rules should be reintroduced stating:

Another student had the same opinion stating:

For these students and others, they believed that enforcing the previous more flexible approach was fairer, as they felt it was unfair to punish all students for a select few who misused their phones. For them, phone misuse should be dealt with on a case-by-case basis.

Another student outlined how technology has a big part for learning in the classroom:

Other students believed that it was important that students are educated about how to be safer online, specifically taught skills on how to identify harmful content, and what they should do if they encounter such content. Students stated that social media is not the problem, rather it’s adolescents’ lack of knowledge on how to navigate it safely:

Other students believed that putting resources into smartphone bans was not beneficial, as resources need to be put into digital education instead:

Students wanted the government to issue advice via an awareness campaign to children and adolescents across the country on how they could stay safe online. This student wanted children and adolescents to know practical skills to be safe online and provided one example of this:

Overall, students did not support the idea of a smartphone ban and the use of resources to implement that ban. Instead, they had practical solutions to issues around smartphone use in schools, with the majority of students feeling strongly that education rather than a ban or restrictive approach was the best solution to keeping them safe. They emphasised that they needed to be prepared for the challenges they would meet online in the future.

Study Limitations

This is a qualitative study; therefore, it would not be appropriate to generalise findings although the insights and experiences shared by participants in this study may be transferable. Furthermore, we did not involve parents who may have other experiences and perceptions to add to our understanding. Please note that we did interview teachers on their experiences of smartphone bans in schools, but the findings are not part of this report. However, we will report on teachers’ experiences in a separate research output. All the schools in our sample were located on the East coast of the country in rural towns and suburban areas, so further research should involve schools from a wider area and both rural as well as urban populations. Finally, most of our participants were female and there were no students identified to the researchers with special educational needs which should be addressed in any further studies.

Conclusion

Students’ smartphone use has been questioned in recent years, as some adults believe children and adolescents’ smartphone use is harmful to their mental health, disruptive to learning and contributes to cyberbullying and problematic internet use (Duke & Montag, 2017; Elhai et al., 2016; Škařupová et al., 2016). Based on these beliefs, which are often expressed in the absence of research evidence, some schools and parent groups have started to introduce approaches to ban or restrict the presence of smartphones from schools. Aligned with this, some reporting about smartphones may unwittingly perpetuate a disproportionate feeling of fear that smartphones alone threaten the wellbeing of children and adolescents (Etchells, 2024; Ogers, 2024). Propagating such negative perceptions clouds the responsibilities of social media companies and governments, as it is an easier solution to ban smartphones rather delving deeper into the issues at hand. Further, by negating responsibilities of these stakeholders, we are not making these online spaces safer, which is then compounded by not teaching adolescents key critical digital citizenship skills, which is a key issue at hand.

Both primary and post-primary students have clearly outlined that they have not been consulted about the implementation of smartphone bans nor had their feedback been sought in a meaningful way since bans had been implemented. Mindful of the rights afforded to children and adolescents under Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Irish Second-Level Students Union have stated that they have not been consulted by the Department of Education on proposals to ban smartphones (McTaggart, 2024). In addition, Article 12 clearly outlines that children and adolescents’ opinions must be considered and considered in all matters affecting them, which is also supported by Ireland’s National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making (Department of Children and Youth Affairs, 2019). Hence, it is important that we listen to the voice of children and adolescents on this issue now, as they do not feel that so far that their voices have been heard by those in positions of authority.

Students provided a nuanced view on smartphones, clearly stating that smartphones should not be used in classrooms, unless it is to assist with their learning. Further, students felt that previous school rules on smartphones provided a fairer approach in schools, as those who broke the rules were then punished. Whereas now, students feel that the teachers do not trust them, and they are being punished for a small minority who broke the rules on phone use. This feeling of mistrust is further compounded by teachers undertaking spot checks in students’ personal belongings. Whilst schools are well-intentioned in trying to tackle misuse of smartphones in schools and protect students, smartphone bans may have an unintended negative impact on students-teacher relations and the culture within schools.

Within this study, post-primary students mainly used smartphones as a tool to be social with friends, entertainment and have autonomy within their lives, which is supported by previous research (Ricoy et al., 2022). In the view of students, smartphones are a positive addition in their lives. However, they acknowledge that social media can be negative, but they have an interesting perspective that like most things in life, there are both positive and negative aspects. With this, students stressed that they need to be taught how to navigate these spaces safely, which is supported by experts in the field (Campbell et al., 2024). In addition, students have stressed that smartphones are a major concern or talking point for adults, but for students, such a ban does not change how disempowered and disrespected they feel on this issue.

It is evident from discussions with primary school students that they have less reasons to use phones. Overall, primary school students acknowledged that they did not need the smartphone during the school day, but in some instances, they needed their phone for safety, specifically for travelling to and from school. Thus, highlighting how a smartphone is used for safety, with a secondary use for connecting with friends. Primary school students have not yet developed the same level of independence as post-primary students and their social interactions currently do not require the phone to facilitate this (e.g., connecting with friends outside of school).

Overall, the responses from participants in this study did not conclusively demonstrate that smartphone bans are having positive impacts for students in the schools where the research was undertaken. According to students, the bans are not preventing cyberbullying, as in their opinion cyberbullying is not occurring amongst their cohort. Students clearly stated that the bans just move any cyberbullying behaviour until after school. Further, students indicated that the ban does not promote socialising amongst students. In addition, some students feel that bans have not improved their mental health, as it has caused some isolation and anxiety for students in the schools that participated in this study.

It is evident from international research and the findings from the current study, that smartphone bans in their current form do not achieve the intended objectives and in fact may be having unintended negative impacts, particularly for students and the school environment. Given that schools already incorporate devices into classrooms and under the Government’s ‘Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027’ are tasked with preparing students for blended lives, decisions to restrict or ban smartphone use at school seem at odds with schools’ obligations to teach students about responsibly using technology, which will in turn address cyberbullying and student wellbeing (Campbell et al., 2024).

Recommendations

The findings above demonstrate the complexity of students’ experiences of smartphone bans implemented within their schools. However, these findings, along with the advice provided by the students to the Minister for Education, has assisted us in proposing evidence-based recommendations below for future research, adolescent voice and education.

Recommendation 1: Evidence Informed Policy

Policy on smartphone use among children and adolescents should be informed by research evidence. This will ensure that a policy is sustainable and relevant to the experiences and concerns of children and adults alike. We recommend the following in relation to future research on this issue:

- Undertake a follow-up study with the schools who took part in this study to understand teachers and students’ experiences of the bans as time has progressed, especially exploring whether bans have been rolled back or adjusted since their implementation.

- There is a need for a co-participatory study with adolescents on how they would implement smartphone rules in schools and what they want to see in online safety education.

- A deeper ethnographic study in one school to understand the impact of smartphone bans on students.

- Qualitative study with parents to explore their experiences with smartphone bans and concerns around children and adolescents being online.

Recommendation 2: Digital Citizenship Education

The Government is currently rolling out its ‘Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027’ and has already significantly invested in the development of online safety resources through Webwise and other programmes for schools. However, students reported that they were not particularly aware of these. Digital citizenship education should be elevated as a compulsory topic that is delivered to all students at primary and post-primary. Such education could incrementally increase as students approach the end of primary school. The focus of this education should be on digital literacy and digital citizenship. Ongoing support for school staff who deliver the education programmes will be required as well as monitoring of the use and effectiveness of resources provided to schools.

Recommendation 3: Empowering Student Voice

While the Minister has established a dedicated unit in the Department of Education to enhance students’ participation in decision making, it is clear from the findings of this study that students were not consulted about the introduction of a smartphone ban in their schools, before or even after bans had been implemented. The ongoing work in the Department of Education on student participation should be accelerated to ensure greater participation in decisions about smartphone use in schools and in the ongoing evaluation of policy in this area.

Recommendation 4: National Awareness Campaign

A national awareness campaign should be rolled out to build knowledge and understanding of smartphones and social media amongst children, adolescents and parents. The campaign could provide accessible and age-appropriate safety tips for children and adolescents on how to be safe online. This campaign must be research informed and provide a balanced view on the positives and negatives of smartphones and social media platforms to ensure that children and adolescents feel that their usage of both are not continuously problematised. Children and adolescents should be consulted on any national campaign that is aimed at their peer group, as they will be knowledgeable in informing whether the campaign is appropriate. In addition, the message of the campaign should be evidence based and balanced.

Recommendation 5: Regulation of Social Media

Children and adolescents in this study expressed considerable trust in social media companies as arbitrators of content and risk mitigation. Consequently, this points to the immense responsibility and privileged position that is enjoyed by these companies. It would seem appropriate then that social media companies double their efforts to ensure that harmful content is never recommended to children and adolescents and that appropriate authorities such as Coimisiún na Meán monitor and regulate for this.

References

Beland, L. P., & Murphy, R. (2016). Ill communication: technology, distraction & student performance. Labour Economics, 41, 61-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.04.004

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019a). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589-597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., Terry, G.: Answers to frequently asked questions about thematic analysis (2019b). Retrieved from https://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/psych/about/our-research/documents/Answers%20to%20frequently%20asked%20questions%20about%20thematic%20analysis%20April%202019.pdf

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association.

Brewer, J. (2014). Don’t ban smartphones in Australian high schools: Here’s why (and what we can do instead). EduResearch Matters, Australian Association for Research in Education. https://www.aare. edu.au/blog/?p=3066

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391-1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

Campbell, M., Edwards, E. J., Pennell, D., Poed, S., Lister, V., Gillett-Swan, J., … & Nguyen, T. A. (2024). Evidence for and against banning mobile phones in schools: A scoping review. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 34(3), 242-265. https://doi. org/10.1177/20556365241270394

Chlup, D. T., & Collins, T. E. (2010). Breaking the ice: using ice-breakers and re-energizers with adult learners. Adult Learning, 21(3-4), 34-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104515951002100305

Department of Children and Youth Affairs. (2019). National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/9128db-national-strategy-on-children-and-young-peoples-participation-in-dec/

Department of Children and Youth Affairs. (2012). Guidance for developing ethical research projects involving children. Available from: https://www.atu.ie/app/uploads/2024/12/ethics-guidance-for-projects-working-with-children.pdf

Department of Education. (2023). Keeping Childhood Smartphone Free: A guide for parents and parents’ associations who wish to engage with their school community regarding internet safety and access to smartphones for primary school children. Available from: https://assets.gov.ie/static/documents/keeping-childhood-smartphone-free-1188d886-b17f-4f77-afe3-a4628c281ad0.pdf

Duke, É., & Montag, C. (2017). Smartphone addiction, daily interruptions and selfreported productivity. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 6, 90-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2017.07.002

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., & Hall, B. J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 509-516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.079

Ellis, D. A. (2019). Are smartphones really that bad? Improving the psychological measurement of technology-related behaviors. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 60-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.006

Etchells, P. (2024). Unlocked: the real science of screen time (and how to spend it better). Hachette UK.

Ferguson, C. J., Kaye, L. K., Branley-Bell, D., & Markey, P. (2024). There is no evidence that time spent on social media is correlated with adolescent mental health problems: findings from a meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. Retrieved from: https://www.christopherjferguson.com/Social%20Media%20Meta.pdf

Gao, Q., Yan, Z., Wei, C., Liang, Y., & Mo, L. (2017). Three different roles, five different aspects: Differences and similarities in viewing school mobile phone policies among teachers, parents, and students. Computers & Education, 106, 13-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.11.007

Goodyear, V. A., & Armour, K. M. (2021). Young People’s health-related learning through social media: What do teachers need to know?. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103340

Goodyear, V.A., Randhawa, A., Adab,P., Al-Janabi, H., Fenton, S., Jones,K., Michail, M., Morrison, B., Patterson, P., Quinlan, J., Sitch, A., Twardochleb, R., Wade, M. & Pallanc, M. (2025). School phone policies and their association with mental wellbeing, phone use, and social media use (SMART Schools): a cross-sectional observational study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, 101211. Published Online. DOI: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101211.

Howlett, G., & Waemusa, Z. (2019). 21st century learning skills and autonomy: Students’ perceptions of mobile devices in the Thai EFL Context. Teaching English with Technology, 19(1), 72–85. Accessed on: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1204626.pdf

Ivie, E. J., Pettitt, A., Moses, L. J., & Allen, N. B. (2020). A meta-analysis of the association between adolescent social media use and depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 165-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.014

Kaye, L. K., Orben, A., Ellis, D., Hunter, S., & Houghton, S. (2020). The conceptual and methodological mayhem of “screen time”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103661

Kemp, P.E.J., Brock, R., & O’Brien, A. (2024, Feb 15). Mobile Phone Bans in Schools: Impact on achievement. British Educational Research Association. Retrieved from: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/mobile-phone-bans-in-schools-impact-on-achievement

Kessel, D., Hardardottir, H. L., & Tyrefors, B. (2020). The impact of banning mobile phones in Swedish secondary schools. Economics of Education Review, 77, 102009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102009

Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927-942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033

McTaggart, M. (2024). Secondary school students have ‘major logistical concerns’ over proposed smartphone ban, union says. Irish Independent. Available from: https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/secondary-school-students-have-major-logistical-concerns-over-proposed-smartphone-ban-union-says/a1451705484.html

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2023). Social media and adolescent health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27396

National Advisory Council for Online Safety. (2021). Report of a National Survey of Children, their Parents and Adults regarding Online Safety. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/204409/b9ab5dbd-8fdc-4f97-abfc-a88afb2f6e6f.pdf

OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en.

Odgers, C. L. (2024). The Panic Over Smartphones Doesn’t Help Teens. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2024/05/candice-odgers-teenssmartphones/678433/

Ofcom. (2023). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes. Retrieved from: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/255852/childrens-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2023.pdf

Ofcom. (2021). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2020/21. Retrieved from: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/media-use-and-attitudes/media-habits-children/children-and-parents-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2021

Ott, T., Magnusson, A. G., Weilenmann, A., & Hård af Segerstad, Y. (2018). “It must not disturb, it’s as simple as that”: Students’ voices on mobile phones in the infrastructure for learning in Swedish upper secondary school. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 517-536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9615-0

Pichel, R., Foody, M., O’Higgins Norman, J., Feijóo, S., Varela, J., & Rial, A. (2021). Bullying, cyberbullying and the overlap: What does age have to do with it?. Sustainability, 13(15), 8527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158527

Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2017). A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis: quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychological science, 28(2), 204-215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616678438

Randhawa, A., Pallan, M., Twardochleb, R., Adab, P., Al-Janabi, H., Fenton, S., … & Goodyear, V. A. (2024). Secondary school smartphone policies in England: a descriptive analysis of how schools rationalize, design, and implement restrictive and permissive phone policies. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2024.2363204

Ricoy, M. C., Martínez-Carrera, S., & Martínez-Carrera, I. (2022). Social overview of smartphone use by teenagers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15068. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph192215068

Rose, S. E., Gears, A., & Taylor, J. (2022). What are parents’ and children’s co‐constructed views on mobile phone use and policies in school?. Children & Society, 36(6), 1418-1433. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12583

Sewall, C. J., Bear, T. M., Merranko, J., & Rosen, D. (2020). How psychosocial well-being and usage amount predict inaccuracies in retrospective estimates of digital technology use. Mobile Media & Communication, 8(3), 379-399. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157920902830

Škařupová, K., Ólafsson, K., & Blinka, L. (2016). The effect of smartphone use on trends in European adolescents’ excessive Internet use. Behaviour & information technology, 35(1), 68- 74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2015.1114144

Smith, P. K., Smith, C., Osborn, R., & Samara, M. (2008). A content analysis of school antibullying policies: progress and limitations. Educational Psychology in Practice, 24(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360701661165

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617723376

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. (2023). Global Monitoring Report 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.unesco.org/gem-report/en

Vuorre, M., & Przybylski, A. K. (2023). A multiverse analysis of the associations between internet use and well-being. Retrieved from: https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/a-multiverse-analysis-of-the-associations-between-internet-use-an

Walker, R. (2013). ‘I don’t think I would be where I am right now’. Pupil perspectives on using mobile devices for learning. Association for Learning Technology Journal. Research in Learning Technology, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21i0.22116

Wolke, D., Lee, K., & Guy, A. (2017). Cyberbullying: a storm in a teacup?. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 899-908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-0954-6

Wood, G., Goodyear, V., Adab, P., Al-Janabi, H., Fenton, S., Jones, K., … & Pallan, M. (2023). Protocol: Smartphones, social Media and Adolescent mental well-being: the impact of school policies Restricting dayTime use—protocol for a natural experimental observational study using mixed methods at secondary schools in England (SMART Schools Study). BMJ Open, 13(7). https://doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmjopen-2023-075832

Appendices

Appendix 1. Parental/Guardian Consent Form

Consent Form for Parents/Guardians (Focus Group)

Appendix 2. Participant Assent Form for Ages 10-14

Participant Assent Form for Focus Group (Ages 10-14)

Appendix 3. Participant Assent Form for Ages (15-18)

Participant Assent Form for Focus Group (Ages 15-18)

Appendix 4. Interview Schedule for Participants

Using of Phone Pouch

- What are the rules?

- Do they stop you using your phone?

- Were you asked about your opinion of the mobile phone rules in school?

- What do you think of the mobile phone rules?/What have you thought about the mobile phone rules?

- Do you like/not like it?

- Why do you like/not like it?

- Do you think it is fair that phones are banned in school?

- Why/why not?

- Do you believe that the phone rules have been good for you?

- Do you believe that your grades are better?

- Do you believe that you can pay attention in class better?

- Do you believe that the phone rules have been bad?

- Any other ways to that you might not use phones in schools?

Taught about Technology Use and Bullying

- Are you taught about online safety?

- Are you taught about cyberbullying?

- Do you think you should be taught about cyberbullying/online safety?

- Would you like to learn more about it?

Participation Feedback

- How do you feel about being in this study?

- Was it fun?

- Was it boring?

- Did we miss any other questions to ask you?

- Anything else you would like to tell us about the mobile phone rules in school?