Most students who are bullied do not report their experiences to adults. This was true 30 years ago when I endured middle school and our research shows it largely continues to this day. I remember being surprised (though maybe I shouldn’t have been) to learn from our first pilot study undertaken 15 years ago that fewer than 15% of those who had been cyberbullied told an adult about it (10% informed a parent while 5% reported it to the school). This made me realize right away that there was a story that needed to be told. And that we needed to do something to improve reporting.

Since then Sameer and I have surveyed more than 20,000 middle and high school students from around the United States. In every one of those studies we ask students who had been bullied or cyberbullied who they told about it. Most often over the years, students tell us that when they do tell someone about being bullied, it is a friend. For example, in our 2010 study of about 4,500 students, 39% told a friend (compared to 18% who told a parent). But something changed in our most recent survey (from late 2016). Recently, it appears at least, more students are turning to adults when they are bullied or cyberbullied.

Trends in Reporting Experiences with Cyberbullying

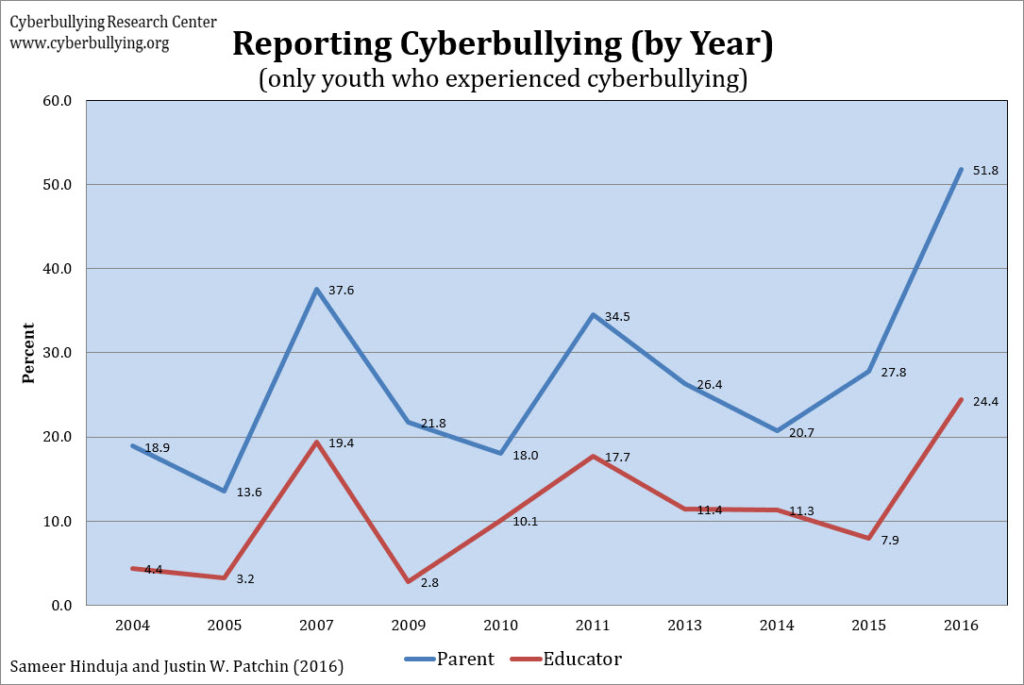

On average, between 2004 and 2015, about 25% of students who were cyberbullied told their parent about the experience (and about 10% told someone at school). This increased markedly in our 2016 survey: About 52% told a parent and about 25% told an educator. We’re not exactly sure what explains the dramatic increase—and we don’t want to jump to any conclusions based on just one data point—but this could be a signal of something positive.

Digging into the latest data a bit more deeply we can see that, in general, boys were less likely to have told someone else about their experiences with others. For example, 57% of girls and 47% of boys told their parent. Interestingly, though, boys were more likely than girls to tell a teacher about being cyberbullied (21% compared to 15%). White students were significantly more likely to tell a parent than non-white students (54% compared to 47%), though there was no difference with respect to telling a teacher. Finally, heterosexual students were significantly more likely to report cyberbullying to parents and teachers than non-heterosexual students (parents: 54% vs. 39%; teacher: 19% vs. 9%). Further exploration of the reporting practices of subgroups of students (particularly those who are often marginalized) is necessary to better understand the motivations for reporting (or not reporting) experiences with bullying.

Reasons for Refusing to Report

Despite the apparent recent improvement, many youth still decline to report their bullying and cyberbullying experiences to adults. A logical follow-up question is: “Why not?” The simple answer is that they are afraid that it is just going to get worse. In their own words from our 2016 study:

“Nobody has done anything about it in the past, so telling would only make it worse.” (17 year-old boy)

“Telling a teacher at school just makes it worse and then everyone laughs at you for telling.” (14 year-old boy)

“No one will do anything and mostly, if I tell anyone the bullying gets much worse.” (17 year-old girl)

“I was afraid telling my parents would make it worse and make people bully me more.” (16 year-old girl)

In short, they believe that the bullying will continue, even if (maybe even especially if) an adult gets involved. The bullying may become less conspicuous, but it will persist—if not amplify. They are also concerned that parents will respond to reports of cyberbullying by taking away technology. “If you’re being bullied on Instagram,” the logic goes, “just stay off Instagram!” Of course one can still be bullied on Instagram without being on the app—rumors could be spread, photos could be posted, fake profiles could be created—and all of this will likely rear itself at school the next day. So even if the target doesn’t have to experience it online, they will still have to face the consequences. More importantly, why should the person being bullied have to stay off of Instagram? They didn’t do anything wrong.

Improve Reporting by Improving Responses to Bullying

The absolute key to getting students to report bullying is to improve responses. You have to remember that when I child is bullied and they turn to an adult for help, all they want is for the bullying to stop. They often don’t even want the person doing the bullying to get in trouble. They simply want the bullying to end. Parents, educators, and other adults tasked with responding to bullying incidents need to keep this in mind, and respond in a way that stops the bullying.

Of course that can be more difficult than it sounds, but the mission should remain constant. Stopping bullying might involve discipline, but it doesn’t have to. It could be as simple as communicating to the one doing the bullying that their behaviors are wrong, hurtful, and unacceptable. Give them an opportunity to do the right thing by stopping. If they don’t, additional actions will need to be taken to ensure they do. Don’t give up! Pull any levers necessary (family or school-based) to stop the mistreatment. And don’t be afraid to be creative. Relying on excessively punitive, deterrence-based punishment isn’t likely to be effective. Our research has found that informal sanctions by parents and schools have a stronger preventive effect than formal penalties. Utilize logical and reasonable consequences for misbehaviors. We have some starter suggestions for you here.

In addition, many schools now use anonymous reporting systems to encourage students to make them aware of incidents. Our conversations with educators in schools with these services suggest they are a valuable tool to coax students into disclosing disruptive behaviors affecting their ability to learn. Encouraging reporting is an important first step, but effectively responding to those reports is essential to develop and maintain a culture where bullying isn’t tolerated by all members of the school community.

The bottom line is, if parents and teachers quickly and quietly stop bullying every time it is reported to them, children and students would run to them for help more frequently—and much sooner—than they do now. This would enable adults to help stop the behaviors before they escalate to the point of tragedy. So it is on us, as adults, to demonstrate to youth that we can come through for them.

It is a bit reassuring that when we asked students who had been cyberbullied to tell us what worked to stop the cyberbullying, “telling a parent” ranked as the third-most successful step taken (school intervention ranked sixth). That said, still only about 17% of youth overall said that telling a parent was an effective response. So, to summarize, about half of those cyberbullied tell an adult about it (an improvement over previous years, but still disappointing). And fewer than one in five said telling a parent helped stop the cyberbullying. I encourage you do your part to increase these statistics even more. If we constantly implore students to talk to us as their “trusted adult,” we have to be more successful in ensuring an effective resolution to the problem. And as we do, more youth will be comfortable reaching out for help – knowing that doing so won’t be in vain.