Aim The aim of this study was to analyse the impact of Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) on the lives of young people and identify factors that promote resilience to mental health difficulties within this population. Methods The study used a mixed methods approach. Results from the analysis of data from a longitudinal population-based birth cohort, the Avon longitudinal Study of Parents and Children {n=6,902) were synthesised with qualitative data from a purposive sample of 11 young people with clinically diagnosed DCD aged 11 to 16 years. Findings from the qualitative study highlighted areas that were important in the lives of the young people interviewed. These areas, such as the importance of friendship groups, bullying and a positive sense of self, were added to the final analytical model as explanatory mediators in the relationship between DCD and mental health difficulties. Findings In total, 123 young people (1.8% of the eligible cohort aged seven years), met all four diagnostic aThis thesis presents research that explored the nature of bullying amongst girls aged 12 to 15 years old in Northern Ireland. The aim of the research was to provide insight into bullying amongst girls of this age through investigating types of female friendships and the impact they may have on the ways in which girls can experience bullying. The roles adopted by girls in relation to bullying are seen from multiple viewpoints of bully, target and bystander. Furthermore, the thesis considers the relatively new phenomenon of ‘cyberbullying’ by exploring how girls use technology such as mobile phones and the Internet in their everyday lives and how this technology offers new and alternative ways to participate in and experience bullying. In order to investigate the participants’ different perceptions and experiences of bullying. Goffman’s theory of social interactions as a performance has been used as an analytical framework. The study sample consisted of 494 questionnaire responses from girls aged 12 to 15 years old across eight schools in Northern Ireland, and eight semi-structured interviews conducted online using instant messenger. A social networking site, Bebo, was used to communicate more widely with possible participants. The study found that the majority of girls have been a target of bullying at some stage with participants reporting experiences involving a diverse range of methods. The findings provide insight regarding the methods girls use to bully and how age is a significant factor regarding the ways in which girls tend to participate in bullying. The study found that over ninety five percent of participants owned a mobile phone and had internet access at home. As these technologies may be used as alternative ways to bully, it is important that adults understand this new area in order to assist girls in their experiences of bullying.

criteria for DCD using strict (5th centile) cut-offs (severe DCD). In addition, 346 young people met wider inclusion criteria (15th centile of a motor test and activity of daily living scales) and were defined as having moderate or severe DCD. These young people with moderate or severe DCD had increased odds of difficulties in attention, short-term memory, social communication, non-verbal skills, reading and spelling. They also had increased odds of self-reported depression, odds ratio: 2.08 (95% confidence interval (Cl) 1.36 to 3.19) and parent reported mental health difficulties, odds ratio: 4.23 (95% Cl 3.10 to 5.77) at age nine to ten years. The young people interviewed did not see themselves as disabled. Factors that increased a positive sense of self were inclusion in friendship groups, information that helped them understand their difficulties and being understood by parents and teachers. These findings were mirrored in the quantitative analysis which showed that the odds of mental health difficulties reduced after accounting for social communication difficulties, bullying, lower verbal intelligence and self-esteem. Conclusions Developmental Coordination Disorder is a common developmental disorder in childhood. The difficulties seen in these young people are complex and assessment needs to be multidisciplinary and consider neurological causes of poor motor coordination, the presence of coexisting developmental difficulties and associated mental health difficulties. Due to the high prevalence of the condition, ongoing one-to-one therapeutic interventions are not feasible. School based interventions, using therapists as trainers, working within a socio-medical model of disability, could work to promote resilience within the individual and improve the acceptance of differences in abilities within the school.

Search Results for “2024 Newest SHRM SHRM-SCP Test Vce Free 🩺 Go to website { www.pdfvce.com } open and search for ▷ SHRM-SCP ◁ to download for free 👓SHRM-SCP New Dumps Book”

ABC were delighted to attend Webwise’s #Connected launch at Twitter EMEA in Dublin ahead of Safer Internet Day 2020.

Webwise launched a comprehensive classroom resource addressing Digital Media Literacy called “Connected”. Connected is a series of interactive lessons for young people in the Junior Cycle. In the lessons, young people discuss and learn about issues relating to understanding and navigating the digital media world such as: digital rights and responsibilities, how data is acquired and analysed by digital media companies, managing their digital wellbeing, and taking a proactive stance on tackling cyberbullying.

Coinciding with Webwise’s launch, ABC had been inspecting a newer social media App called “TikTok”.

TikTok is a video making and sharing social platform that is increasingly popular with young people between the ages of 8 and 12. ABC’s Dr. Tijana Milosevic had consulted with Irish media outlets about the rising popularity of TikTok prior to Internet Safety Day, and identified the possibility of users posting mean comments in young user’s video posts.

Though little is known about the implications of TikTok from an empirical research point of view, it was suggested that young people may be using the platform for empowerment.

This empowerment could involve expressions of identity, creativity, talent, viewpoints and vulnerabilities. These can easily be expressed by young users using TikTok’s creative video making features, and the ease of spreading the created video across all major online platforms including: Facebook, WhatsApp, Gmail and Twitter.

ABC added TikTok to its “App Watch” component on TackleBullying.ie which is Ireland’s National Anti-Bullying Website for young people, parents and teachers.

Bullying has been a source of disquiet, if not moral panic, in recent years. Yet pupil experience outside the classroom has rarely been given the attention it deserves in educational research devoted to the problem. This study examines the social relations between pupils in the lower years of a mixed, multicultural, inner city school. It is based upon long term participant observation as a teacher researcher and aims to develop a sociological appreciation of aggression and bullying during school-day free-time. Part One explains the origins of the research. Recent studies of ‘cussing’ (verbal abuse), fighting (a topic which has hitherto received very little attention), and bullying are then examined in detail. The research seeks to identify the links, if any, between hostile social relations in school and broader social inequalities at a societal level. Further, it aims to tease out ways in which micro level divisions of power within the pupils’ social world shape, and are used by children within interactions. Close attention is therefore given to the meaning, or meanings, of the term ‘power’. Models of relative power which inform research focusing upon pupil experience are also identified. In Part Two, both the research site, City School, and the research techniques used are described. Cussing, fighting and bullying, forms of aggressive interaction which distress pupils and obstruct the achievement of curricular goals, are then examined closely. Consideration of gender, ‘race’ and age grading provides a sharper awareness of underlying power divisions and of how these constrain opportunities for the relatively weak. In Part Three, ways of improving the quality of experience available for pupils during school-day free-time are identified. Whilst the complexity of this task is acknowledged, the study concludes with a renewed sense of optimism about what may be achieved when teachers are more effectively equipped with the skills to understand and, where necessary, make sensitive interventions.

Throughout the last twenty years, following accession to the European Union (EU), legal economic migrants (and their families) have the right to live and work in European member states. Economic migrants who are European citizens of member states now assume immigrant status and co-exist in countries with pre-existing immigrant communities that have affiliations to the former British Empire. With demographic composition changes of immigrant communities in Europe, difference and discrimination of populations from diverse cultural backgrounds has become a focal issue for European societies. A new, multi-ethnic Europe has thus emerged as one context for understanding cultural uncertainties associated with youth and migration at the end of the twentieth century and the start of the twenty first century. These uncertainties are often associated with the impact of new nationalisms and xenophobic anxieties which impact mobility, young people, and their families (Ahmed, 2008; Blunt, 2005). In this dissertation I seek to examine young peoples’ experiences of migration and school exclusion as they pertain to particular groups of immigrant and minority ethnic groups in England. In particular, the study explores the perceptions and experiences of two groups of diverse young people: British ‘minority ethnic’ and more recently migrated Eastern European ‘immigrant’ youth between the ages of 12-16. It provides some account of the ways in which migrant youth’s experiences with both potential inclusion and exclusion within the English educational system, particularly in relation to the comparative and temporal dimensions of migration. Young people’s opinions of inclusion and exclusion within the English educational system are explored in particular, drawing, in part, upon the framework of Critical Race Theory (CRT) and other theoretical positions on ethnicity and migration in order to paint a picture of contemporary race relations and migration in Buckinghamshire county schools. The methodological approach is ethnographic and was carried out using qualitative ethnographic methods in two case secondary schools. The experiences and perceptions of 30 young people were examined for this research. Altogether, 11 student participants had Eastern European immigrant backgrounds and 19 had British minority ethnic backgrounds (e.g. Afro Caribbean heritage, Pakistani/South Asia heritage, and African heritage). The methods used to elicit data included focus groups, field observations, diaries, photo elicitation, and semi-structured interviews. Pseudonyms are used throughout to ensure the anonymity of participants and to consider the sensitivity of the socio-cultural context showcased in this dissertation. Findings of the study revealed that Eastern European immigrants and British minority ethnic young people express diverse experiences of inclusion and exclusion in their schooling and local communities, as well as different patterns of racism and desires to be connected to the nation. The denial of racism and the acceptance of British norms were dominant strategies for seeking approval amongst peers in the Eastern European context. Many of the Eastern European immigrant young people offered stories of hardship, boredom and insecurity when reflecting on their memories of post-communist migration. In contrast, British minority ethnic young people identified culture shock and idealised diasporic family tales when reflecting on their memories of their families’ experiences of post-colonial migration. In the schooling environment both Eastern European immigrants and British minority ethnic young people experienced exclusion through the use of racist humour. Moreover, language and accents formed the basis for racial bullying towards Eastern European immigrant young people. While Eastern European immigrant youths wanted to forget their EU past, British minority ethnic young people experienced racial bullying with respect to being a visible minority, as well as in relation to the cultural inheritance of language and accents. The main findings of the research are that British minority ethnic young people and Eastern European immigrant young people conceptualise race and race relations in English schools in terms of their historical experiences of migration and in relation to their need to belong and to be recognised, primarily as English, which is arguably something that seems to reflect a stronghold of nationalist ideals in many EU countries as well as the United Kingdom (UK). Both of these contemporary groups of young people attempted both, paradoxically, to deny and accept what seems to them as the natural consequences of racism: that is racism as a national norm. The findings of this study ultimately point towards the conflicts between the politics of borderland mentalities emerging in the EU and the ways in which any given country addresses the idea of the legitimate citizen and the ‘immigrant’ as deeply inherited and often sedimented nationalist norms which remain, in many cases, as traces of earlier notions of empire (W. Brown, 2010; Maylor, 2010; A. Pilkington, 2003; H. Pilkington, Omel’chenko, & Garifzianova, 2010).

#BeKindOnline – Safer Internet Day 2021

To mark Safer Internet Day, the Irish Safer Internet Centre invite you to the launch of the #BeKindOnline Webinar Series on Tuesday, 9 February at 2pm.

Register for the Safer Internet Day 2021 Launch Event

Launch Event

Minister for Justice, Helen McEntee TD, will deliver the opening remarks to launch Safer Internet Day 2021 before commencing Coco’s Law, or the Harassment, Harmful Communications and Related Offences Bill.

Professor Brian O’Neill (member of the National Advisory Council for Online Safety) will then host a panel discussion with the Irish Safer Internet Centre partners, including:

- Chief Executive of ISPCC Childline, John Church;

- CEO of the National Parents Council Primary, Áine Lynch;

- Project Officer of Webwise (PDST Technology in Education), Jane McGarrigle; and

- Chief Executive of Hotline.ie, Ana Niculescu

#BeKindOnline Webinar Series

As part of Safer Internet Day, the Irish Safer Internet Centre will also host a series of webinars to help keep you and your families safe online:

Tuesday, 9 February: 7.30pm-8.15pm

- Title: Empowering Healthy Online Behaviour in Teenagers

- Guest Speaker: Dr Nicola Fox Hamilton, Cyberpsychology Researcher, member of the Cyberpsychology Research Group at the University of Wolverhampton and lectures in Cyberpsychology and Psychology in IADT, Dun Laoghaire.

- Audience: This webinar is for parents of teenagers.

- Register: here

Wednesday, 10 February 7.30pm-8.15pm

- Title: Empowering Healthy Online Behaviour in Younger Children

- Guest Speaker: Mark Smyth, Consultant Clinical Psychologist

- Audience: This webinar is for parents of younger children.

- Register: here

Thursday, 11 February 7.30pm-8.15pm

- Title: Empowering students to build digital resilience and manage their online wellbeing

- Guest Speakers: Jane McGarrigle and Tracy Hogan (Webwise)

- Audience: This webinar is for teachers, educators, school leaders and education stakeholders.

- Register: here

About the Irish Safer Internet Centre

The Irish Safer Internet Centre exists to promote a safer and better use of the internet and digital technologies among children and young people. Co-ordinated by the Department of Justice, the Irish Safer Internet Centre partners are:

- ISPCC Childline: www.ispcc.ie/childline

- National Parents Council Primary: www.npc.ie/primary

- Webwise (PDST Technology in Education): www.webwise.ie

- Hotline.ie: www.hotline.ie

We look forward to welcoming you.

In the third chapter, the results from a pilot study are presented, the first to be conducted in Ireland. It examines results obtained from 30 self-selected victims, who were interviewed and given a personality test (Cattells’ 16PF5). Factors contributing to bullying and the effects of bullying were explored, as were the victims’ personality and their perception of the situation. Organisational factors such as stressful and hostile working environments, also the senior position of bullies, their aggressive behaviour and personality were cited by victims as reasons for being bullied. Most victims reported psychological effects ranging from anxiety to fear, and physical effects ranging from disturbed sleep to behavioural effects such as eating disorders. In relation to personality, many victims felt they were different, and we found to be anxious, apprehensive, sensitive and emotionally unstable. Action taken by victims ranged from consulting personnel to taking early retirement. The aim of the investigation reported in Chapter Four was to extend the pilot study and to attempt to make up for its limitations. Thus, a control group of non-victims was employed, the number of respondents was increased, interviews were conducted in the workplace, and a revised interview schedule and a more appropriate personality test were included. The sample comprised 60 victims and 60 non-victims, employees from two large organisations in Dublin. Both samples responded to a semi-structured questionnaire and completed the ICES Personality inventory (Bartram, 1994; 1998). Results showed that victims were less independent and extraverted, more unstable and more conscientious than non-victims. The results strongly suggested that personality does play a role in workplace bullying and that personality traits may give an indication of those in an organisation who are most likely to be bullied. In an extension to the main enquiry, the history of respondents with regard to their experience of bullying at school was examined. Four groups were formed: (1) those who had been bullied both at school and at work, (2) those who had been bullied at work, but not at school, (3) those who had been bullied at school but not at work, and (4) those who had not been bullied at school or at work. The test results from each group showed that the victim profile was most marked for Group One; Group Four were non-victims throughout their lives; Group Three also produced non-victim profiles; Group Two were most similar to Group One. In interpreting these findings it is tentatively suggested that Group Three (those without the typical personality characteristics of a victim) were able to shrug off the bullying they experienced at school, whilst Group two had possibly escaped bullying at school because of the support available to them from family and friends, and from being team members of school debating societies and sports teams, support that was no longer available when they were adults. A subsidiary pilot study of Chapter Four re-assessed victims with additional tests of the Interpersonal Behavioural Survey and the Culture-Free Self-Esteem Inventories, second edition. Results indicated that again, victims had high dependency and in addition, low self-esteem and direct aggression, poor assertiveness and a tendency to denial and to avoiding conflict. Chapter Five represents an attempt to examine the personality characteristics of bullies, using the ICES and IBS and a behavioural workplace questionnaire (BWQ). Although it proved difficult to obtain a large enough sample of bullies, findings were encouraging. Bullies proved to be aggressive hostile individuals, high in extraversion and independence. They were egocentric and selfish, without much concern for other’s opinions. Most bullies said that they themselves had been bullied at work. Chapter Six extends the personality profiles of bullies and victims to consider their behaviour.

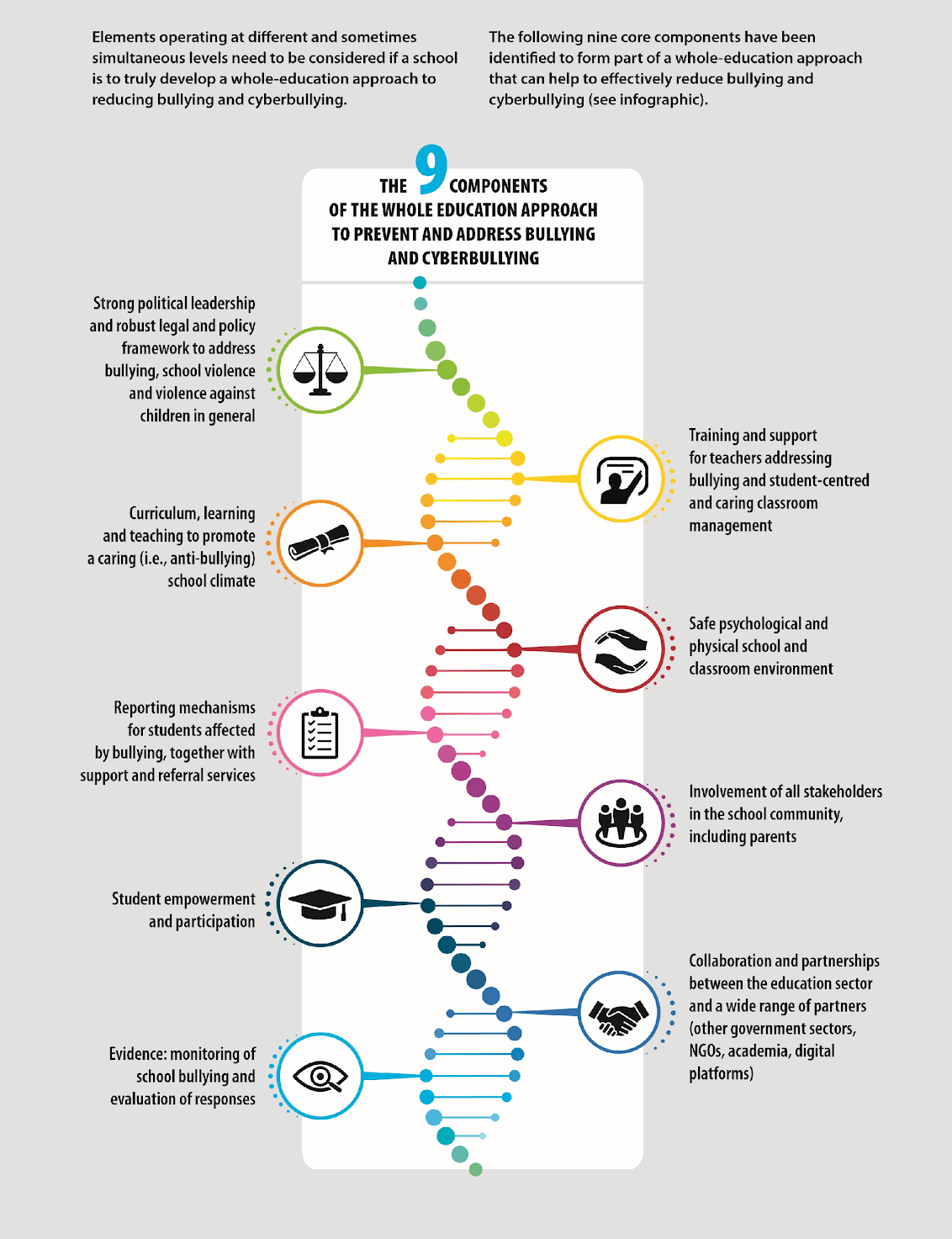

International research suggests that successful initiatives aimed at tackling school bullying and cyberbullying are delivered as part of a whole-school approach. However, these whole-school based initiatives have been limited in their success because they have failed to recognise that the local school exists within a wider education system and community that is supported and maintained by society.

Consequently, the Scientific Committee proposes that an effective response to bullying and cyberbullying should be described as a “whole-education approach”. A whole-education approach ensures that local school initiatives recognise the importance of the interconnectedness of the school with the wider community including education, technological and societal systems, values and pressures, all of which can impact on the prevalence and type of bullying and cyberbullying that occurs in a school.

Characteristics of the whole-education approach

This whole-education approach to reducing violence and bullying in schools including cyberbullying is holistic as it provides a comprehensive and systemic framework including legal and policy influence that are beyond a whole-school approach. This approach to reducing bullying contributes to the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular SDG4, which aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education, and SDG16, which aims to promote peaceful and inclusive societies. By proposing this broader approach to school bullying, the education system can be even more inclusive and sustainable for the future.

The Scientific Committee recognizes the following pre-requisites that ensure that the whole-education approach to bullying and cyberbullying has a wide national coverage, is sustainable, inclusive and benefits all children, and is comprehensively implemented across the entire school system.

- Each of the nine components is important and necessary but not sufficient alone. These should be considered as integrated elements of the whole-education approach. A coherent combination of these nine components will enhance the long-term effectiveness of responses to bullying. In summary, the 9 core components of a whole-education approach are not a menu (or ‘shopping list’) from which only some aspects can be selected to reduce bullying.

- It is necessary to plan and implement well-coordinated systematic actions that are sustainable. Once-off measures are not effective.

- This places a greater emphasis on the significance of the whole system of education underlying the commitment not only to help students involved in bullying (perpetrators and targets alike) but to make the entire education system better equipped to reduce violence, bullying, and cyberbullying among learners.

- National or sub-national education authorities should design programmes that can be effectively implemented in all schools and across the network of relationships attached to schools.

- Education authorities should support schools, with the implementation of bullying prevention programmes with guidance and resources.

- Children and young people need to be centrally involved in designing, implementing and evaluating the nine components of the whole-education approach. Schools exist for children and young people and need to be involved in an age-appropriate manner to develop and implement the whole-education approach.

- A whole-education approach, along with addressing directly bullying, should also explicitly promote positive, respectful and caring interactions.

KEY MESSAGES ON EACH COMPONENT OF THE WHOLE-EDUCATION APPROACH

STRONG POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND ROBUST LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK TO ADDRESS BULLYING, SCHOOL VIOLENCE, AND VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN GENERAL

- National leadership is critical, as well as leadership all the way down to the school level, to champion a strong response to bullying, school violence, and violence against children in general.

- Anti-bullying laws, policies, frameworks and guidelines should be provided at a national level with corresponding policies at the local and school levels.

- There should be laws and policies on inclusive education that address identity-based bullying (for example race or sexuality). These should be translated into explicit policies against discrimination at the local and school levels. ⮴ Laws, policies, frameworks and guidelines should evolve and be adapted to new forms of school aggression such as cyberbullying.

TRAINING AND SUPPORT FOR TEACHERS ON BULLYING AND STUDENT-CENTRED AND CARING CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

- Teachers should be supported through training, mentoring and accessing resources such as appropriate teaching & learning materials to foster a student-centred and caring school environment.

- There should be pre- and in-service training to increase teachers’ familiarity with bullying prevention and intervention and to learn about how to achieve student-centred and caring classroom management and school environment.

CURRICULUM, LEARNING & TEACHING TO PROMOTE CARING (I.E., ANTI-BULLYING) SCHOOL CLIMATE

- To reduce bullying, schools need to provide a student-centred and caring school climate. ⮴ Curriculum, learning and teaching, plus teacher-student relationships should all be geared towards fostering a student-centred and caring school environment.

- To achieve this, student-centred teaching and learning is essential.

SAFE PSYCHOLOGICAL AND PHYSICAL SCHOOL AND CLASSROOM ENVIRONMENT

- Education authorities, school principals and other school staff should create an environment where students and the whole school community feel safe, secure, welcomed and supported.

- All school staff, not only teachers, should be sensitized and supported to foster a caring school environment free of bullying.

- The school leadership needs to model caring relationships. Authoritative, democratic leadership should be promoted by principals, boards, teachers and other staff.

- Every bullying situation should be recognized and responded to in a timely, consistent and effective way.

REPORTING MECHANISMS FOR STUDENTS AFFECTED BY BULLYING, TOGETHER WITHSUPPORT AND REFERRAL SERVICES

- Schools should have staff responsible for monitoring bullying.

- Reporting channels and mechanisms need to be consistent and known by the whole school community, appropriate to different ages, and confidential.

- The school system should be integrated with community support and referral services that are known by and accessible to the school community.

- Students (in particular but not exclusively targets and bystanders) as well as school staff should feel they can talk about bullying to a trusted person known to them, in the school or outside the school.

- Collaboration should be established with social media platforms to ensure that school communities have effective channels to report cyberbullying.

INVOLVEMENT OF ALL STAKEHOLDERS IN THE SCHOOL COMMUNITY, INCLUDING PARENTS

- All stakeholders in the school community should be involved in anti-bullying initiatives including principals and board, teachers, other school staff, students, and parents, together with other stakeholders in the wider community, such as children and adults who participate in extra-curricular activities, e.g. sports, arts, etc.

- Parents, including groups such as Parent Teacher Associations, should be supported to engage on the issue of bullying.

STUDENT EMPOWERMENT AND PARTICIPATION

- Bullying is a relational phenomenon that occurs within a network of people; thus, all students should be involved in prevention programs instead of focusing only on perpetrators or targets.

- Bystanders play a key role in the dynamics of bullying and should be empowered to support students targeted by bullying.

- Attention should be paid to the involvement of students who belong to a minority group in the design and implementation of bullying prevention strategies, to ensure these strategies are inclusive of all students.

- Student-led initiatives and peer approaches to prevent bullying should be implemented in conjunction with programmes involving school staff and other adults.

COLLABORATION AND PARTNERSHIPS BETWEEN THE EDUCATION SECTOR AND A WIDE RANGE OF PARTNERS (OTHER GOVERNMENT SECTORS, NGOS, ACADEMIA, DIGITAL PLATFORMS)

- education authorities should effectively collaborate with different sectors including health, social services, etc.

- Other relevant sectors should provide resources and support to reduce bullying and cyberbullying, including social media companies

- Collaboration between the educational sector and academia should be fostered to enable research to better understand bullying and how to reduce it.

EVIDENCE: MONITORING OF SCHOOL BULLYING AND EVALUATION OF RESPONSES

- It is essential to monitor bullying within schools and across the education system.

- Regular assessment of the effectiveness of preventative and intervention measures at a school and system level is essential.

- Monitoring and assessment should involve both students and school staff and should include questions about the school climate.

Colm Canning

Education Project Coordinator Dublin City University

The DCU Anti-Bullying Centre (ABC) has published the symposium report Re-Imagining Ethics and Research with Children, following a groundbreaking event held on 29 April 2024 at DCU’s All Hallows Campus. The symposium brought together researchers, educators, and professionals from institutions such as Dublin City University, University College Dublin, Barnardos Ireland, and Webwise to explore the ethical challenges of conducting research with children.

Key discussions at the event focused on child-centred and rights-based research methodologies, aligning with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Participants discussed issues of informed consent, power dynamics in research spaces, and the role of children as active contributors rather than passive subjects.

The symposium was opened by Prof. Anne Looney, Executive Dean of the DCU Institute of Education, who emphasised the importance of bridging policy and practice in ethical research. The discussions highlighted the need for reflexivity, adaptability, and participatory approaches that ensure children’s voices are respected and influence decision-making.

The full symposium report, authored by Dr Sinan Aşçı, Dr Megan Reynolds, Dr Sayani Basak, Dr Maryam Esfandiari, and Prof James O’Higgins Norman, is now available.

Read the full report here.